* Indicates a note at the end of the blog

When Meg Page, townswoman, friend of Alice Ford, mother of Anne Page and a merry wife of one of Windsor’s leading merchants, one of the two Merry Wives of Windsor, receives a letter professing love from the dissolute hustler knight Sir John Falstaff, she recognizes at once that he is proposing an illicit sexual liaison. She is cheerfully affronted. She wonders what she might have done that he would dare to “assay” her “in this manner” (2,1,24). “What should I say to him?” she wonders. And then she says, “Why, I’ll exhibit a bill in the parliament for the putting down of men.”

In Elizabeth’s time there was a parliament (from the French parler, to talk), which she summoned when she needed a consensus of courtiers for some decision or financial matter. It met some 13 or 14 times during her reign. It consisted only of men above a certain income, who could be elected only by other men of a certain status and income. Despite having a female monarch there were no women members of parliament.* So Meg Page is making a joke, that must have felt quite tired, when she talks about a bill for the putting down of men. Her point, I think, is that Falstaff’s behavior is not unique and reflects something about the attitudes and behavior of men in the society of Elizabethan Windsor. She wants to have revenge on men in general, though she also makes it clear that Falstaff will be an individual target: “For revenged I will be, as sure as his guts are made of puddings.” (2,1,29-30) Since Mistress Ford, also a townswoman and wife of a wealthy Windsor merchant, receives an almost identical letter, the two friends plot their revenge on Falstaff which culminates, in the final act, in the masque of Herne the Hunter.

The revenge plots of the two women tell us a great deal about the irony of women’s position in Elizabethan England. The irony arises from the significant gap, between the formal, legal position of women as the property of their fathers or their husbands with no guaranteed right to govern their own destiny or act in relation to social organisations, and their actual willingness and power to get things done and to wield sweeping influence over society as a whole and their husbands and friends in particular.

It is the two wives who decide to act against the bumbling intruder. Mistress Ford does not wish to take the issue to her husband because she knows he does not have the rationality or perception to understand the situation, let alone do something about it. And besides, he torments himself with his imagined cuckoldry,** fearing what it might do to his reputation and therefore the basis of his trade and wealth, and both fearing and taking pleasure in the erotic threat and promise of his wife sleeping with someone else. When Ford decides to up the ante by creating the persona of yet another lover, Mr Brook (note the wateriness of both names), he creates a complex voyeurism through which to experience Alice’s sexuality.

Ultimately, when the third stage of revenge takes place in Windsor Great Park, it is the women who lead the action. Page and Ford both demur to their wives. And when the comic solution is offered at the end, the “breaking bread” together, it is Meg Page and not her husband who invites everyone to “laugh this sport o’er by a country fire”. (5,5,241)

The wives are not the only women who drive the action of the play. Mistress Quickly is a wonderfully Octopus-like creation. Her aspirations and her fingers are everywhere. She intrudes in the guise of helping, she is both a busy-body and a woman who survives financially and socially by making conflicting alliances with everyone. She acts as go-between for Falstaff and the wives, hoping that they won’t spot her as the double agent (the wives do, Falstaff doesn’t). She also acts as marital go-between for all the men (indeed almost all the men with the exception of Falstaff) who are seeking Mistress Anne Page’s hand in marriage. She persuades each one in turn that she has their interests at heart and that Anne (or Nan) will choose him, and the money rolls in and her abundant ego swells.

And Anne Page is also a woman of action (or girl – I can never work out quite how old she is. Fourteen or fifteen?). She is aware of the limitations and potential of each of the men who comes a-courting. When her father announces that the effete and self-absorbed Slender is his choice, she says “Good mother, do not marry me to yond fool.” And then, in one of the best lines in the play, when her mother says she seeks a better husband and Mistress Quickly interprets this to mean Dr Caius, Anne says: “Alas. I had rather be set quick i’th’earth, and bowled to death with turnips!” (3,4,85-90).***

But it is in her relationship with Fenton that Anne shows her spirit most clearly. At the beginning of the play he pursues her with diffidence and a kind of passive acceptance, as though he is unable to effect the situation. He says to Anne, “I see I cannot get thy father’s love, therefore no more turn me to him, sweet Nan” (3,4,1-2), and Anne’s response is to tell him to keep trying. She pokes him to act in his own behalf, she draws from him a realization that he loves her for herself and not (just) for her father’s money. She transforms him into an active partner when they contrive to ditch the favored courtiers of mother and father and to get married independently. Fenton, the only character in the play who undergoes substantial change, is transformed into the man (or boy) who lectures the father at the end: “You do amaze her. Hear the truth of it…” (5,5,219)

So, the women in the play are the actors, working through informal means to preserve their own interests and advance the welfare of society. But there are other dimensions of women’s position that are revealed and explored in Merry Wives. It is important for us to understand that it is in a society where women exercise their power from behind, clandestinely, that men like Sir John Falstaff will behave as he does. Falstaff’s ill-conceived plan to board one or both of the women (as though they were ships), get his stones off, so to speak, and most importantly gain access to their husbands’ money, depends firstly on his belief that women have real control over their husbands’ purses, and secondly on a somewhat contemptuous perception of married women as sexually promiscuous. It is both telling and alarming that despite legal changes in society over the four centuries since the play was written, women still earn less than men, are still seen by men in power as fair game, as wanting it, as property and objects of both desire and derision. #Metoo has been a long time coming, and we can only work toward a time when women will have their revenge on the Trumps and Johnsons and Kavanaughs of this world.

The irony of Falstaff’s plan is twofold: firstly, Master Ford, exploring his private obsession with the thought that his wife is unfaithful – or might be – offers Falstaff a far easier and less messy access to his money than Alice Ford does; and secondly, it is Ford himself who is convinced that his wife is promiscuous; furthermore, he gets off on it. It cannot escape the audiences for this play that when Ford enjoins his friends, including the Welsh parson, his neighbor Master Page, and the French Doctor Caius, to pore with their hands through the contents of the buck(laundry)basket which contains her underwear, and to delve into the smallest nooks and crannies of the house – the woman’s domain, identified in a metaphorical sense with her body – until they find evidence of the fat intruder, he is inviting the men of the neighborhood to become intimate with his wife.

Shakespeare has a full, complex, multi-layered appreciation and understanding of women. It is true and disappointing that there are too few female characters in his plays. But oh my, the ones we have are wonderfully rich. Merry Wives is a beguiling, funny and engaging play, and the wives themselves share with other women in Shakespeare an intelligence and practicality that makes them great theatrical characters and real ones too.

* Quite apart from Merry Wives, Britain became the constitutional monarchy we know today – in which the royal family has very limited power, though elected representatives must swear an oath of allegiance to the reigning monarch – through a long and gradual process beginning with the English Civil War in the mid 17th century and the Act of Union with Scotland in 1701. Britain did not become a democracy until the Reform Act of 1918 gave women the right to vote, and the Parliament Acts of 1911 and 1949 reduced the power of the hereditary House of Lords to veto bills passed in the House of Commons. The first woman elected to the UK parliament was a member of Sinn Fein and did not take her seat: Lady Constance Markievicz in 1918. The first woman to be elected and actually sit in parliament was Nancy Astor, an American who married Viscount Astor when she was 26.

** From Old French cucuauld, which itself comes from cucu, or cuckoo, a bird with a habit of laying its eggs in another bird’s nest.

*** I wonder if this runs parallel to the Jarramplas festival in the village of Piornal in Southwest Spain in which “hundreds of people have been running through the streets of a tiny town in southwestern Spain, chasing a fancy-dressed, beast-like figure and pelting it with turnips”. (https://www.mcall.com/sdut-spanish-town-celebrates-bizarre-turnip-throwing-2016jan20-story.html)

As a visual spectacle, The Merry Wives of Windsor is little more than knockabout comedy. It ranges from farce to the subtle humor of gesture. It’s good knockabout, mind you, and despite the preposterous improbability of the plot it is vastly entertaining. Its theater is very domestic and in this respect it can be linked to the comedies of manners of the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. It abounds in the details of domestic life and as a central theme explores the forces, such as virtue and faithfulness (honesty), that keep daily life on a more-or-less even keel. In the life of the town that is at the center of the play conflict is almost always settled with food. A “hot venison pasty to dinner” is offered as a palliative to Justice Shallow, who fumes that he has been wronged. It is Master Page’s belief that they will “drink down all unkindness.” And at the end of the play, despite the substance of Falstaff’s intrusive campaign against the women, Mistress Page shakes it off and says, “Good husband, let us everyone go home, and laugh this sport o’er by a country fire”.

As a visual spectacle, The Merry Wives of Windsor is little more than knockabout comedy. It ranges from farce to the subtle humor of gesture. It’s good knockabout, mind you, and despite the preposterous improbability of the plot it is vastly entertaining. Its theater is very domestic and in this respect it can be linked to the comedies of manners of the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. It abounds in the details of domestic life and as a central theme explores the forces, such as virtue and faithfulness (honesty), that keep daily life on a more-or-less even keel. In the life of the town that is at the center of the play conflict is almost always settled with food. A “hot venison pasty to dinner” is offered as a palliative to Justice Shallow, who fumes that he has been wronged. It is Master Page’s belief that they will “drink down all unkindness.” And at the end of the play, despite the substance of Falstaff’s intrusive campaign against the women, Mistress Page shakes it off and says, “Good husband, let us everyone go home, and laugh this sport o’er by a country fire”.

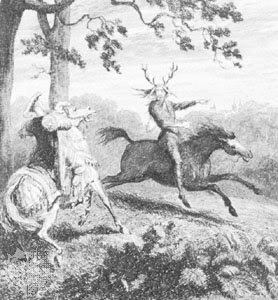

In the fifth act of Merry Wives the play turns into a carnival of English folklore. The children of the town, with Sir Hugh as their coach and Mistress Quickly as the Faerie Queen, become fairies who torment Falstaff as punishment for his lust-fueled pursuit of two of Windsor’s upstanding middle-class wives. The only other play in which fairies feature so prominently is A Midsummer Night’s Dream, where their role is somewhat different, though comparably dark. Falstaff himself, at the suggestion of the Windsor wives, is dressed as a character in English pagan mythology, Herne the Hunter. With horns on his head he suffers the fate that Master Ford imagined for himself: a cuckold – traditionally wearing horns – being physically tortured and publicly humiliated. He is removed from the town, which embodies the values of rationality and moral certainty, to the country, in which the bestial forces of desire and greed are exposed. As Mistress Page says to her husband: “Do not these fair yokes / Become the forest better than the town?” (5.5.103-4)

In the fifth act of Merry Wives the play turns into a carnival of English folklore. The children of the town, with Sir Hugh as their coach and Mistress Quickly as the Faerie Queen, become fairies who torment Falstaff as punishment for his lust-fueled pursuit of two of Windsor’s upstanding middle-class wives. The only other play in which fairies feature so prominently is A Midsummer Night’s Dream, where their role is somewhat different, though comparably dark. Falstaff himself, at the suggestion of the Windsor wives, is dressed as a character in English pagan mythology, Herne the Hunter. With horns on his head he suffers the fate that Master Ford imagined for himself: a cuckold – traditionally wearing horns – being physically tortured and publicly humiliated. He is removed from the town, which embodies the values of rationality and moral certainty, to the country, in which the bestial forces of desire and greed are exposed. As Mistress Page says to her husband: “Do not these fair yokes / Become the forest better than the town?” (5.5.103-4)